To Live and Die in Yosemite

Returning to Yosemite National Park after a decade away. Connecting with new friends, remembering old ones, and feeling the spirits of those who left us in the days between.

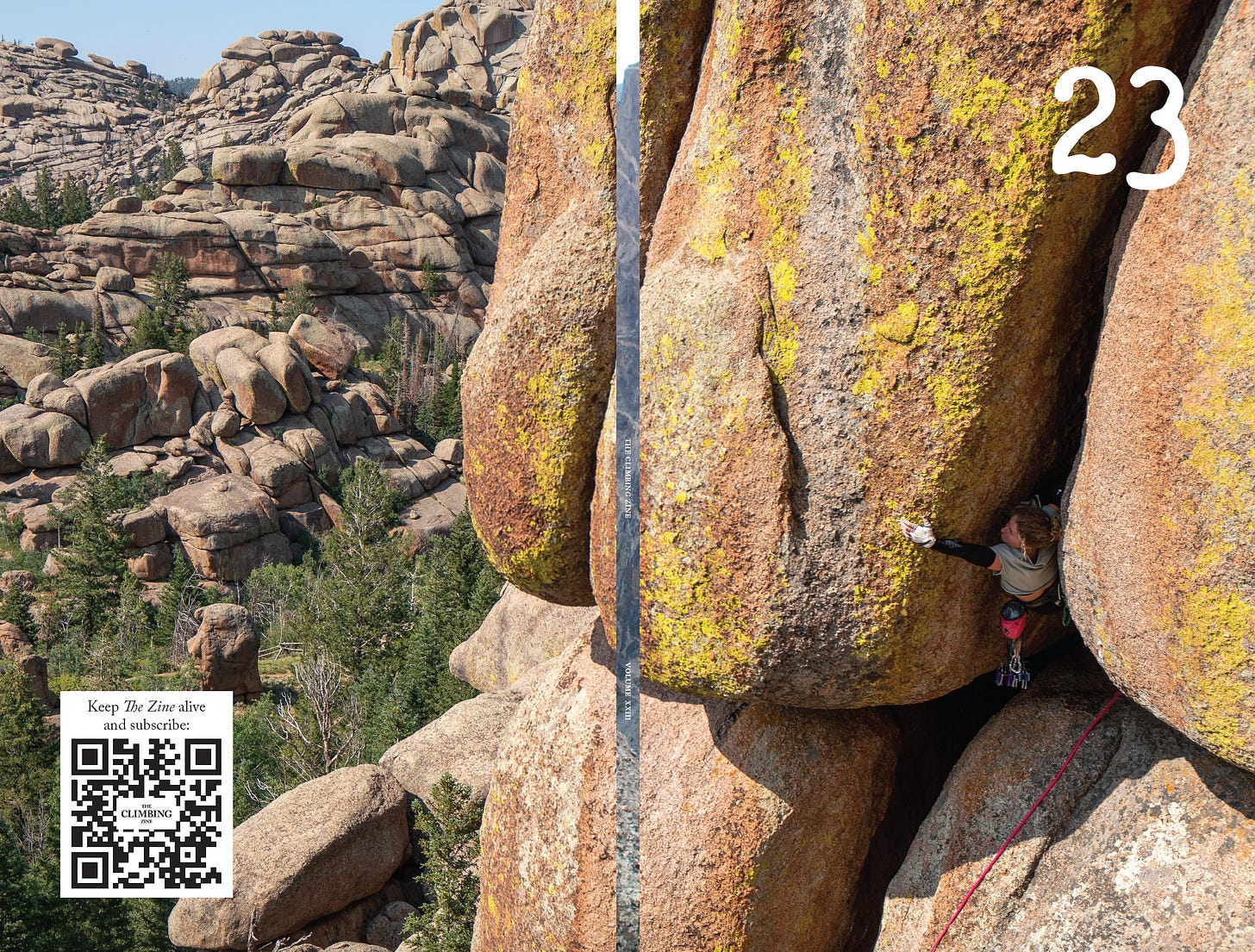

Preface: This is the most recent long form essay that I’ve written. It is published in the current issue of The Climbing Zine, Volume 23.

I’ve included some annotated links for fun.

I wanted to get a few of my more recent essays up on this page, to get a reference point for my work on this site. Soon, I’m going to start sharing pieces just for the Substack page, as I figure out exactly how I want to publish here.

I hope you enjoy this one.

If you’d prefer to listen to me read this story, you can do so here, via our Dirtbag State of Mind podcast.

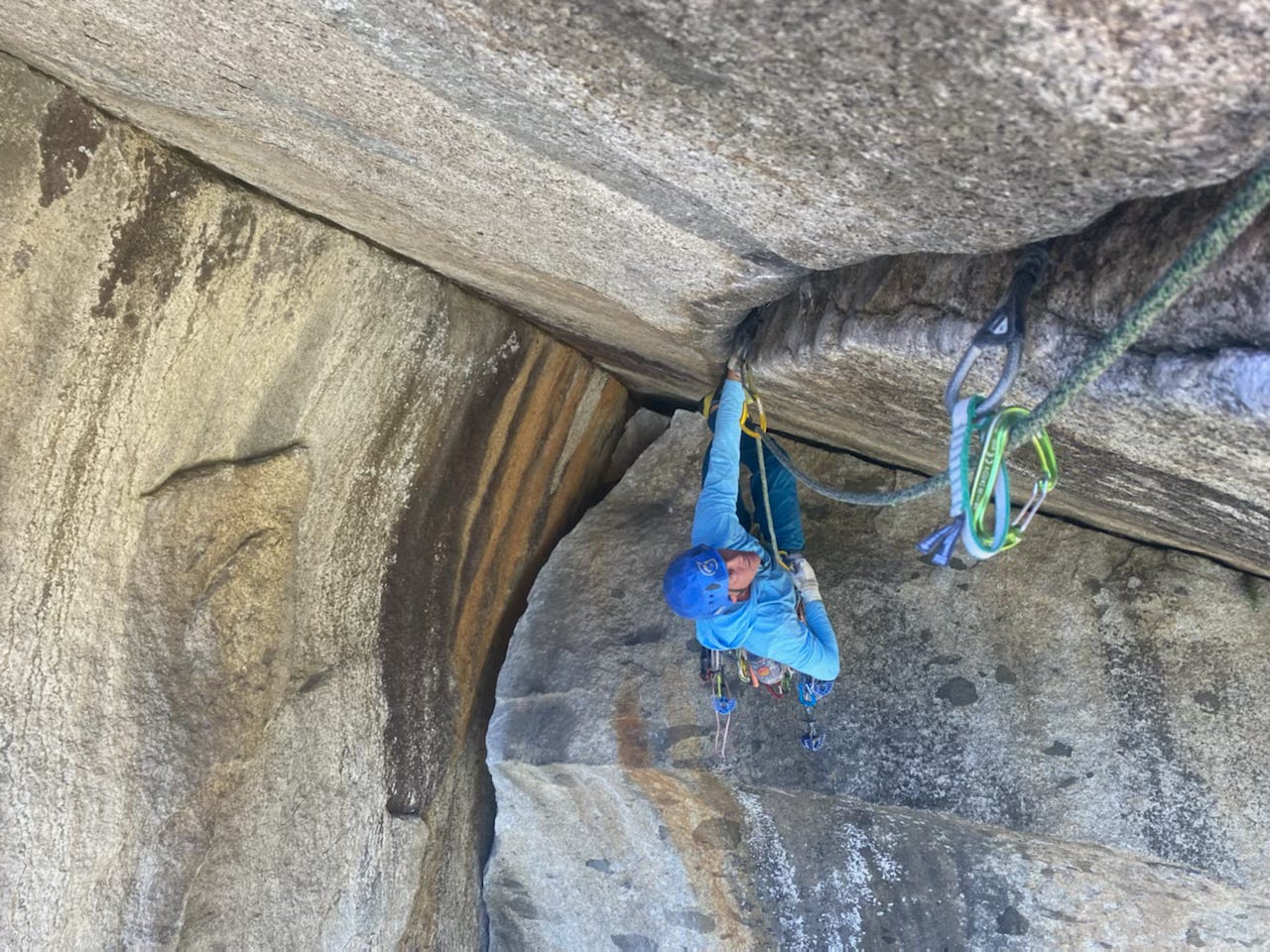

Though I’ve been dangling off the cliffs of Yosemite for twenty-plus years now, I couldn’t help but feel overwhelmed with intimidation at the base of the roof crack known as Separate Reality.

Taylor and I had just rappelled in, and it was his lead, which was just fine with me. Taylor is a relatively new climbing partner, and he’s about ten years younger than me. Most of my regular climbing partners go back as long as I’ve been climbing, back to where it all began in Gunnison, Colorado. All of my best friends are also my best climbing partners.

Tying in with someone is a great act of faith and trust. I don’t think it can be overstated, and some climbers can be too casual about this. Perhaps I’ve got mental battle scars from all my near misses over the years. If I tie in with you, I trust you. And if that trust is broken, well, it’s a hard thing to get back.

For the last couple years, Taylor and I have really been clicking. I’ve needed that. I’m in my early forties, and many of my climbing partners have started families, and thus they have less free time for trips. That’s not to say I don’t climb with my friends who have kids—many are still quite motivated—it’s just changed up the rotation a bit.

This was my first trip back to Yosemite in almost a decade. For the first ten years or so of my climbing life I was obsessed with Yosemite, obsessed with learning how to live and climb on a wall. Those days, with my best of friends, led to the best experiences, now my treasured memories and stories.

Those Yosemite days culminated in an ascent of the Salathe Wall on El Capitan. Nothing fancy, not even close to free, but we clawed our way up it, and it felt like a once-in-a-lifetime accomplishment.

And then I moved to Durango and got obsessed with The Creek. I was tired of poop tubes, portaledges, haul bags, and all the other elements that make big wall climbing seem like a construction gig. I wanted a different kind of fight, a different kind of glory, and I found it on those crimson walls of Wingate that seem to be endless in the land that is now Bears Ears National Monument.

It was the Yosemite Facelift that brought me back to The Valley. Ten years before when we did the Salathe, we just happened to be there when the Facelift was going on, and I was very impressed with the effort. Climbers were all over the Valley cleaning up trash and having a great time doing it. By day, we picked up dirty diapers left on the side of the trail, and by night, we partied down. And in the end, thousands of pounds of trash were cleaned up, leaving Yosemite a lot cleaner than it was before.

I am a very sentimental person, and as I traveled to Yosemite, I thought of everything that had happened in the decade since I’d last been there. I thought of the climbing legends that had died there, especially Dean Potter, who I used to see around all the time there. When I was twenty-two, that was like seeing Michael Jordan next to you on a basketball court.

Since I’d been there, El Cap had been free soloed. The Dawn Wall happened. Countless wildfires had scorched California. I’d been engaged, got a dog, bought a house, called off the engagement, and ended up with partial custody of the dog—a dog named Hope that I completely love and adore. During COVID quaratines, I fell into depression and loneliness; therapy and nature helped crawl out of it.

So many other things happened too, but my mind just started reminiscing in a way that only nature makes it reminisce. Yosemite to me is nothing short of a love affair, and all this sentimentality is connected to this love of land we call Yosemite.

As I left Colorado, people said things like, “I hope it’s not too smokey out there,” or “I just got back from Cali; the air quality was terrible.”

This is the new normal; the global warming stuff they told us would happen in college in my Environmental Studies courses in the early 2000s is now our reality. But for this trip, I got super lucky. An early fall storm rolled in, dropping snow high in the mountains and clearing out the smoke.

I spent my first couple climbing days on the East Side with Mark Grundon, one of my original homeys and climbing partners. Mark and I have always had a great climbing chemistry, and we have both gone down the path of not only establishing new routes but replacing bolts on old ones. We sampled perfect granite and also checked out Clark Canyon, a cool volcanic sport climbing area near his home of Mono Lake. While climbing, we both noted anchors that needed to be replaced and potential for new lines; both of our brains just work that way.

Soon enough it was time to go to Yosemite. The storm had cleared out, and the Facelift was beginning.

When I told people I was going to Yosemite, many asked what my objectives were. And I quickly told them I didn’t have any. I just wanted to be there, like visiting an old friend with no intention other than hanging out.

If we talked a little bit longer, I would reveal I had a small objective: to get on Separate Reality. That climb had lingered in my mind ever since I saw a picture of Wolfgang Güllich free soloing the line in an old climbing magazine. Even decades after seeing that photo, I can still picture it in my mind’s eye, the exposure below, the strength of Wolfgang.

I mentioned the climb to Mark, but he would be working as a guide during the Facelift, so he would only be able to hang out at night and not join me on the climb. I told him maybe I would save the climb, to experience it with him. “Don’t save climbs,” he said, as if it was a motto someone had passed down to him.

I got in my rental truck and drove over Tioga into The Valley. At the moment I was thankful to be alone, thankful for the reflection. I’d never driven into The Valley alone, always with a climbing partner or girlfriend.

The site of the ranger station at the top of the pass was a bit of a buzzkill. When I started climbing in Yosemite, rangers were the enemy. The relationship between climbers and rangers wasn’t great, one that goes back all the way to the societal revolutions of the 1960s. Rangers had rudely awakened me in the middle of the night, tried to bust me with cannabis, and generally were gun-toting assholes who were jealous of the freedom and swagger of dirtbag climbers (or so I thought then).

I aired out the car and got ready for the ranger to approach my ride. He was a jolly, bearded guy, who greeted me with a big smile as I told him I was there for the Facelift. “Do you need a map?” he asked.

“Well, it’s been a decade since I’ve been here, but I think I’m good,” I told him.

“Welcome back, brother!” he said with the utmost sincerity.

The lady at the entrance station quickly waved me through, and the drive shifted back into sentimentality. Yosemite seems to have a different vibe these days, I thought.

Since El Capitan was my goal and singular focus for so long, the sight of it when rolling in always had so much meaning. This day it was magnificent, but I didn’t know what meaning to attach to it. Sure, I’d climbed it, but as Warren Harding said after the first ascent, “It looked to be in better shape than I was.”

Rather than obsessing about a climb, I was simply trying to find my campsite. Since I was a volunteer, and I’d later be presenting a poem on Friday night, I was able to camp for free at a volunteers site. I pulled up the site in my GPS, but as it led me there, all I saw were Do Not Enter signs.

So, I did another lap around the weird roads in The Valley and ended up in the same place. I figured I’d just park the truck and take a little walk to see what I was missing. Yosemite has always been a difficult place to navigate.

As soon as I parked the truck, I ran into my friend Nadine—Taylor’s wife—and she pointed out where the campsite was. It was, in fact, right through those Do Not Enter signs, which were put there to keep the general public out. Ah, Yosemite.

When I finally found my site, I put all my food and smelly things into the bear box, cracked a beer, and decided to go for a stroll to reminisce.

What I experienced that night I can only describe as a flash flood of feelings, like I’d just walked into therapy and my therapist asked me to describe every emotion I’d ever felt while climbing and hanging in Yosemite. Each formation had a story to retell me, like remember when you almost died here, or remember that six-hour belay when you ate a jar of peanut butter with your grime-stained fingers?

The beginning of my Yosemite epic poem is rooted in death. Just a couple weeks before I set sail for The Valley for the first time, my friend Josh had died in a motorcycle accident. He was only twenty, and the very last thing he said to me was, “We’re survivors; we will survive,” and the last words he wrote me were, “Enjoy the promised land,” when I told him I was going to Yosemite.

I don’t know how a twenty-year-old could be so prophetic, but ever since I’d moved out West, my life was full of these strange circumstances, making me think perhaps we are surrounded by spirits and ghosts. All I know is I don’t know enough to truly know about premonitions or if we have an afterlife, but I do know what has been said to me and what has happened to me.

I soaked it all in, and it was all too much. I wished I’d had a trusty friend at my side, but instead I texted those friends, those climbing partners that I share these memories with. I drank sips of beer for those that died here and are no longer with us, for those that would have loved to make it here. Why am I still standing? Didn’t I make similar mistakes? Why was I afforded so many journeys here, on nearly every major formation?

I got hungry and wandered back to camp. After the sun had gone down, I finally made myself a humble meal of pasta. I knew a night of good sleep would settle my mood, and I planned to go for a hike by myself in the morning light to reflect more on a place that held so much of me within it.

In recent years I’ve realized I have a relatively simple recipe for my mental health. Socialization, sleep, a moderately healthy diet, climbing, yoga, acupuncture, and cardio exercise are essential to me. Even just a good hot shower or a comforting show or movie can be a perfect reset.

Before COVID hit, I honestly thought I’d never really experience deep depression again. But I did. It wasn’t just depression—it was numbness.

Throughout the pandemic, all I could really focus on was my business and climbing. Like many dirtbag climbers, I’ve always lived relatively hand to mouth. And I got to a certain point in life where I wanted and needed more than just living paycheck to paycheck. I wanted a house, health insurance, and a successful business. And when all that was threatened, I went into survival mode as if all that mattered was keeping my business alive.

The Zine and the rest of my business did survive, thankfully. I found a therapist when I realized I needed someone to talk to, as to not burden my friends but also to seek out professional help.

Damn, I wish I’d done that twenty years sooner, because I was still carrying pain and baggage from a time period when I was severely depressed and suicidal. I felt that pain deeply in my first few sessions, but then I also felt great light and upliftment as I talked about it and confronted it. I wanted to face my demons, and I was, and that felt good.

The other thing I needed to face again was the stage. Though I am a person who needs just the right amount of alone time, I am also very extroverted. I never truly realized that until everything shut down, and we disconnected from one another. And one of my favorite things in the world is being on a stage, telling a story, or reciting a poem, creating that connection with the audience.

Over years and years, I’d developed a familiarity with being onstage—it’s very similar to leading in climbing, the sharp end—but losing that for a couple years made the stage seem incredibly intimidating again. I guess it was like not leading for years and then trying to get back to it.

For the first couple gigs, the fear and anxiety were almost overwhelming, and I had thoughts of giving up the spoken-word side of my profession. Most of these gigs at climber events don’t pay any money, and it’s an incredible amount of work preparing. For example, I have to practice a poem around fifty to one hundred times to memorize it. But even though these gigs don’t pay, it is my favorite part of my profession; the words born in my poetry are only truly made alive when they are said aloud to an audience. It’s a thrill similar to climbing: living in the moment on the sharp end, living the good life. Never for money, always for love.

Or as Bob Dylan said in his poem “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie”:

And there’s something on yer mind you wanna be saying

That somebody someplace oughta be hearin’

But it’s trapped on yer tongue and sealed in yer head

And it bothers you badly when your layin’ in bed

And no matter how you try you just can’t say it

And yer scared to yer soul you just might forget it

That first day of going on a run/hike up to the top of Yosemite Falls was glorious. As I woke up that morning and threw down a quick breakfast and tea, I realized I’d never even gone on an adventure like this; every single hike I’d ever done in Yosemite had led to a climb.

I was uncertain about my future adventures in Yosemite, really not sure if I’d have any more in store, but that light and energy hit me quickly on the trail. That’s the beauty of love affairs with the natural world: they can be resumed even after a decade pause.

It’s amusing how the mainstream tourists react to us dirtbags on the trail. I was moving as quickly as possible—the trail was so steep it certainly wasn’t running—but it was enough to solicit reactions from some of the people I passed. One guy said, “I’ll catch you; you’ll slow down at the top.”

I didn’t care about passing anyone; I was just going along at the pace of my desire, for the feeling. I was so happy and immediately felt the buzz of running combined with being in one of my favorite places on the planet.

My energy and head space were restored. Later that day, I bought the new Yosemite guidebook. Instead of feeling like I’d done everything in Yosemite I wanted to do, a new door opened. From the looks of the book, there was plenty to keep me occupied for several lifetimes. Plus, I knew I’d gotten better at crack climbing with all the years spent in The Creek in search of the perfect high and line.

When I bought the book, I also saw my own books on the shelf alongside it. Though my books had been for sale there for years, I’d never seen them with my own eyes. What a trip—how surreal it was—my own stories were available to anyone who would take the risk to buy a copy. And I was coming to the realization that as a writer I hadn’t come to the end with El Capitan; it was merely a high point. For a climber, the road goes on forever, and the party never ends, right?

The next day, the day I would perform my poem, I finally got out for a climbing session. I was already tired. The night before at my campsite I was kept awake by a fellow camper who clearly cared more about her cigarettes and boxed wine than any adventure the next day. Sleep is one of the ingredients for me for a happy life, and I was deprived of that. Every time this happens, though, I think of the nights when I was the loud drunk one; surely I kept many a climber awake in the Superbowl campsite at The Creek, back in my party days.

Taylor and I only had a couple hours, so we opted for some cragging at the Cathedral Wall. By happenstance we ended up climbing a 10d corner that I’d done on my first-ever trip to Yosemite. Two Tent Timmy, my best friend, had led it, and I was in awe. He’d only been climbing for a year or so, and I was amazed by how quickly he’d gotten good at it. I could barely follow that pitch then, and even on this day, I noted how tricky it was.

That night, my butterflies calmed down when it was time for my poem. This was what I was used to. If I prepared enough, my mind would get calm. The words are there now. Just like a project, it’s time to give it your best, and when I know I’ve prepared enough, a certain peacefulness comes over me.

I was sharing the stage with Lauren Delaunay Miller and Conrad Anker that evening, an honor all in itself. Timmy O’Neill was the emcee for the evening, and I’ve known him a long time—so long that he remembered that before I became a full-time writer and publisher I was a dishwasher. So that’s how he introduced me, as only Timmy can do, as a “hydro technician of plates” or something like that.

I’d been working through a lot in my life, and onstage in the last year, I’d felt uncomfortable and out of place so many times leading up to this moment. It’s these moments in my life when I question everything and wonder whether I am on the right path, if I’d made the right decisions, if I’d ever be comfortable onstage again.

Starting a memorized poem for me means digging into my mind, giving the audience a gift and an energy, and then sensing what comes back, all while trusting I won’t forget the words. As a sensitive person, I notice the energy intensely. I can tell when people aren’t paying attention or are not into it. It affects the vibration of the words. As I started this one, I felt the crowd hanging on to every word, as if they were uplifting me, as well as the poetry I was delivering.

It’s almost like a magical kiss. Something so ordinary, but when it, connects its heavenly. You’re in the moment. Nothing else matters. You’re living.

The words flowed and connected. It was the feeling I’d been chasing ever since it went away. It was back. I was back. I was in Yosemite and felt deeply connected to the hundreds of people there.

Success to me as a writer means earning my living from it, but it also means this connection to my fellow human beings. And that means sharing it freely; we were all gathered at the Facelift to clean up Yosemite and make it a better place, and yet for me, it was also a reunion. After my poem, I basked in the feeling, the relief that the work was done, and it had gone well.

The next day was my last in Yosemite. Only one day left to climb. I still hadn’t led a pitch yet, and this would only be day two of climbing, but it didn’t matter. All that mattered was the day in front of us.

My granite instincts had all gone away, I told myself. I was fine with my sandstone and limestone, I told myself. I’d done everything I wanted to do on granite in this lifetime, I told myself. But here I was basking in the golden granite, in the sunlight, racking up, the spirit of Yosemite engulfing me.

For our warm-up, we decided to link up the first couple pitches of Reed’s Pinnacle. Luckily Taylor remembered to bring stoppers; I hadn’t used mine in years and forgot to bring them, a foolish move.

I shuffled my way up the granite crack and remembered the art that is granite crack climbing and placing gear in it, looking for that constriction to place a nut or the crystal sticking out to marry momentarily with the rubber on your shoe. After a hundred-some feet, I was pumped and ran out of gear, but it was 5.9 climbing, and I just zoned in; I’ll only ever run it out if I have to.

As it often is, I only really screwed over my second, Taylor, as the pitch ended with a traverse to the anchor and I didn’t put any gear in. Sometimes that forced runout drives the mind to an incredibly focused place.

Taylor made do, as a trad climber does, and climbed safely to my belay. We rapped off, our 80-meter rope barely making it back to our first belay ledge. We packed up, went back to the car, and got ready for Separate Reality.

I’d wanted to do this climb with Mark, as we’d been talking about it for years, and he’d already done it. As a twist of fate, Mark’s back had seized up, and he wasn’t even able to come to The Valley and work that week. I really missed him at all the evening events; we were looking forward to hanging.

But his line—“don’t save climbs”—had even more weight to it. We don’t ever know what tomorrow will bring.

This afternoon brought us to a rappel to a massive, sloping ledge below the roof crack that is Separate Reality. The climb was established by Ron Kauk the year I was born: 1978. It appeared to be even steeper than I could have imagined. Plus the exposure beneath was massive, a thousand feet of air with the Merced River below.

Though I’ve climbed plenty of 12a in my life, I felt incredibly intimated, as intimidated as I felt on my very first trip to Yosemite. Often two climbers will be eager to get the lead, but I had no problem with Taylor taking the sharp end.

The heart of the climb is the roof crack, and the glory is the finish of that crack at the lip, but I’d never known that even the start is tricky, a wide, steep section that’s best to layback. Taylor went up and down but quickly figured out the move and then embarked on the hand jams at the roof. He did quite well, moving efficiently while trying to place the right gear, but he eventually took a whipper at the crux. I caught him, and he figured out the finish.

On toprope, I still felt out of my element and intimidated. Hand jams are hand jams, I told myself, as I dangled there horizontally. I made it to the crux and hung, patient to know that today was a day of reconnaissance and not sending. The final lip was glorious and not as hard as I expected. The seeds had been planted for a project, to return again to Yosemite, someday.

That evening I talked about our glorious failure to any friend who would listen. Failure is so much a part of our process as climbers, yet I don’t know if its highlighted enough when we tell our stories. I’m a master of failure. I even like it. I like discussing it, and even though, like everyone else, I’m a human with an ego, I’ve accepted that most climbing days on a project are training, under the guise of failure.

I only climbed four pitches on this trip, surely the lowest I’d ever done on any Yosemite trip, even the rainy ones. Yet this trip held a richness and a reset that I’m still contemplating and savoring.

I’m still a workout freak; I always need my exercise and routine with climbing and cardio. But I can sense that I’m moving toward a different place—a place of continued striving, but not just striving for the big climb. I did the big climbs. I know what the mountaintop feels like.

Every time I can return to Yosemite, I can visit that feeling, if only briefly. I also know every time I feel the pain of grief, the reality of how close I came to death there, and the constant renewal that nature provides.

Climbers in our forties have all been dealt a hand that had some luck in it. We know how very precious it all is—it can be gone tomorrow. If our bodies are holding up, we can still live out the dreams of our youth. We are the old schoolers who are very much alive and thriving in the new school.

I left for Yosemite with no idea of what the place still meant to me or if any of my climbing dreams still existed there. I came home with the answer that so much of who I became as a human and climber is rooted in Yosemite. I’ll still have projects there as long as I can climb, and at this moment of repose made possible through writing, it seems like the road goes on forever, and the climbing never ends.

Originally published in Volume 23 of The Climbing Zine, our current issue.

I loved this part the most -->

I am a very sentimental person, and as I traveled to Yosemite, I thought of everything that had happened in the decade since I’d last been there. I thought of the climbing legends that had died there, especially Dean Potter, who I used to see around all the time there. When I was twenty-two, that was like seeing Michael Jordan next to you on a basketball court.... So many other things happened too, but my mind just started reminiscing in a way that only nature makes it reminisce. Yosemite to me is nothing short of a love affair, and all this sentimentality is connected to this love of land we call Yosemite.